This article was published online on February 6, 2021.

Last February, on a sunny afternoon in West Hollywood, two girls with precise eye makeup paused on Melrose Avenue and peered in the windows of a building whose interior was painted a bright, happy pink. Two pink, winged unicorns flanked racks of clothes: ribbed crop tops, snakeskin-print pants, white sleeveless bodysuits. One of the girls tugged on the door, then frowned. It was locked, which was weird. She tugged again. Inside, a broad-chested security guard regarded them impassively from behind a pink security desk.

Erin Cullison, the U.S. public-relations rep for PrettyLittleThing, a fast-fashion brand founded in 2012, watched the girls give up and walk away. She sighed. Although the West Hollywood showroom closely resembles a store, it is not, in fact, a store. It is not open to the public; the clothes on the racks don’t have price tags. “People try to give us cash, but we’re not even set up to take money,” Cullison told me. Instead, the clientele is made up of the brand’s influencer partners—thousands of them—who can make an appointment to visit the showroom every couple of weeks and “get gifted.” They try on the latest styles and take advantage of various “photo moments”: lounging on the plush pink couch, posing on the pink staircase, peeking out of the London phone booth repainted—yes—pink. They can snack on a pink-frosted cupcake, and (provided they’re 21 or older) drink a glass of rosé at the store’s pink bar, before heading home with several items of free clothing.

PrettyLittleThing is part of the Boohoo Group, a company that has become a dominant force in retail fashion over the past decade; along with several other aggressive and like-minded companies, it is quickly reshaping the industry. Boohoo stock is now publicly traded on the London Stock Exchange (LSE: BOO), but it started as a family business. As the legend goes, the family patriarch, Abdullah Kamani, immigrated to the U.K. from Kenya in the 1960s and began selling handbags from a street stand. Eventually, he opened a textile factory that supplied the retailers that, starting in the 1990s, shook the fashion world with their cheap clothes and high merchandise turnover: H&M, Topshop, and the Irish fast-fashion juggernaut Primark.

Abdullah’s business was successful enough that he bought himself a Rolls-Royce; his son Mahmud saw the potential for even greater profits. In 2006, Mahmud and his business partner, Carol Kane, began selling cheap clothes directly to consumers through Boohoo.com. Without the burden of retail stores, the company’s costs were relatively low, except when it came to marketing. Young girls who went on YouTube (and, later, Instagram) were inundated with microtargeted ads for Boohoo bodysuits and minidresses. Boohoo’s founders understood that social media could be leveraged to make new brands quickly seem ubiquitous to their target audience. “If you have that imagery out there you are perceived as a much larger business than you actually are,” Kane told the trade publication Drapers.

Social media wasn’t just a convenient place to advertise—it was also changing how we think about our clothes. Fashion brands have always played on our aspirations and insecurities, and on the seemingly innate desire to express ourselves through our clothing. Now those companies had access to their target shoppers not just when they stood below a billboard in SoHo or saw an ad on prime-time TV, but in more intimate spaces and at all hours of the day. Brands flooded our feeds with their wares, whether through their own channels or, more surreptitiously, by enlisting influencers to make an item seem irresistible, or at least unavoidable.

The more we began documenting our own lives for public consumption, meanwhile, the more we became aware of ourselves (and our clothing) being seen. Young people, and young women in particular, came to feel an unspoken obligation not to repeat an #outfitoftheday; according to a 2017 poll, 41 percent of women ages 18 to 25 felt pressure to wear a different outfit every time they went out.

Boohoo’s founders understood that the company had to hustle to keep customers’ attention—to “be fresh all the time,” as Kane has put it. “A traditional retailer might buy three or four styles, but we’ll buy 25,” Kane told The Guardian in 2014. Not having to keep hundreds of stores stocked meant Boohoo could be flexible about inventory management. In 2018, H&M was sitting on $4.3 billion worth of unsold items. Boohoo, by contrast, could order as few as 300 or 500 units of a given style—just enough to see whether it would catch on. Only about a quarter of the initial styles were reordered, according to Kane.

Over time, Boohoo accumulated rich data about online consumer behavior, and further tailored the shopping experience to its shoppers’ tastes. “They know that first-time customers like to see this product category, or customers from this geographic area like this color palette,” Matt Katz, a managing partner at the consulting firm SSA & Company, told me.

In normal times, Boohoo’s agility and ingenuity offered crucial advantages over the competition. When the pandemic hit, those advantages became decisive.

In 2015, when Tricia Panlaqui was 12, she pretended she was 13 so she could start an Instagram account, where she posted videos of herself doing the kinds of things that 12-year-olds do: cartwheeling, blowing kisses at the camera, putting on makeup. By her 15th birthday, she had moved on to what she felt was a more grown-up medium—YouTube—and focused her content on fashion. When she posted haul videos, a YouTube genre that’s a combination of an unboxing and a bedroom fashion show, her viewership skyrocketed. Brands began reaching out, offering her sponsorship deals.

In Tricia’s earliest videos, her outfits had mostly come from familiar mall stores: a white sweater from Express, distressed denim cutoffs from American Eagle. But once she hit 10,000 followers, her channel began to feature clothes from a different set of brands, ones that were typically online-only and based in China. There was Shein, which sells $10 bathing suits, and Zaful, where the prices were even lower. These companies had cropped up alongside lesser-known brands whose names tend to be two words awkwardly jammed together: DressLily, NastyDress, TwinkleDeals, TrendsGal, FairySeason. You wouldn’t find their goods at the mall or see them advertised on TV, but if you were a young woman between the ages of 12 and 22 on social media, their targeted ads were inescapable.

When Tricia agreed to make a video featuring a company’s products, she would typically receive a few hundred dollars’ worth of free merchandise. The product quality could be iffy, but the clothes were cheap and abundant—which meant she could make more haul videos.

There was nothing particularly groundbreaking about Tricia’s fashion sense, or her online persona. She liked iced vanilla lattes from Starbucks and leggings from Lululemon. But she had warm, wide eyes, and she spoke to the camera in a friendly, direct way. The more content she made about shopping, the more views—and ad revenue—she earned. The year Tricia turned 16, she made nearly $40,000 from ad revenue, sponsorships, and commissions; to celebrate her birthday, she showed off her purchases from a shopping spree that had cost her $3,000—all money she had made through her YouTube channel. Once Tricia surpassed 100,000 followers—a key metric for YouTube influencers—she began getting offers from better-known fast-fashion brands, including Boohoo, as well as other companies that were following its digital-first model, such as Princess Polly and Fashion Nova.

To Tricia, sometimes these companies all seemed to be copying one another. Someone would send her a loose tie-front tank top, and then a few days later four other brands would deliver their versions of the same style. She soon had more clothes than she knew what to do with. She gave them to friends and charities and thrift stores; she sold them on the social-shopping app Depop and ran giveaways for her followers. Her closet still overflowed with outfits, so she stuffed the excess into suitcases.

Working with these brands gave her some pause. Cheap clothes come with severe environmental consequences, and this troubled Tricia. (Her sponsors were self-conscious about this too—she says they asked her to hide the plastic packaging their clothes came in so it wouldn’t be visible in the videos.) The industry’s labor practices are also suspect, and commenters chided her for working with companies that had terrible track records. She temporarily cut ties with Shein after it was accused of using child labor in its factories. “But as sad as it is, every brand is doing some type of thing,” she told me. “You’d have to cancel every single brand.”

When the coronavirus arrived, Tricia was worried—with the world falling apart, would anyone care about shopping? Clothing retailers were among the hardest hit by the pandemic. In April, U.S. clothing sales plummeted by 79 percent from March; McKinsey predicted that global fashion-industry revenues would contract by 30 percent in 2020. Brands like Primark were saddled with what one industry observer called an “inventory crisis”—billions of dollars of merchandise intended for now-closed shops.

With less inventory and no brick-and-mortar stores, Boohoo and its competitors had no such drag on their operations. Quick to pivot, the brands sent Tricia sweatpants and hoodies and suggested themes for her videos: Corona style! Lounging at home! Even with the economy in free fall, demand for cheap, cute clothes persisted.

In times of crisis, consumers don’t stop shopping—they just limit their purchases to affordable pleasures. Fast fashion had expanded its market share during the 2008 global financial crisis; now this new cohort of companies—known as ultra-fast fashion—was poised to do the same. While the rest of the retail sector struggled and legacy companies such as J.Crew and Neiman Marcus filed for bankruptcy, many of Tricia’s sponsors and their rivals thrived. Asos’s sales rose rapidly from March to June. Boohoo had its best quarter ever. “We’ve seen an incredible sprint to digital,” Matt Katz told me. “What would’ve taken seven years has taken seven months—or seven weeks.”

Boohoo’s clothes may not feature prominently in Vogue photo shoots, and may, for now, appeal to customers who are mostly under the age of 30. But the rise of ultra-fast fashion marks a major shift in the retail world. Two decades ago, the first fast-fashion companies redrew the lines of a staid industry. Now their faster, cheaper successors are upending it. In the process, they are changing our relationship to shopping, to our clothes, and even to our planet.

Back when going to the mall was still a possibility, Tricia filmed another video. She held up a yellow plastic bag from a former fast-fashion powerhouse, Forever 21. “I normally don’t go there and, like, buy clothes there … but our store was 70 percent off so I was like, ‘Okay,’ ” she said, sounding skeptical.

For those of us who grew up haunting the food courts of suburban malls, Forever 21 was once the epitome of fast fashion. When the company filed for bankruptcy in 2019, some interpreted it as the end of an era. If Millennials killed homeownership, golf, and department stores, perhaps Generation Z consumers, who claimed to prize sustainability and transparency, would be the death of fast fashion. In study after study, young shoppers said they preferred eco-friendly products from socially conscious companies; surely they wouldn’t support an industry notorious for its alarming environmental toll and history of exploiting workers. But that isn’t exactly what happened.

When Forever 21 (then known as Fashion 21) opened its first store—in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, in 1984—the majority of the clothes bought in the U.S. were still produced domestically, and most fashion brands released new styles seasonally. “Your mom took you shopping at the beginning of the school year. You got two pairs of jeans, and maybe if you were really lucky, you could squeeze a dress out of her,” recalls Aja Barber, a writer and fashion-sustainability consultant.

But macro-level changes were transforming the industry. Synthetic fibers made it possible to manufacture cheaper (and in many cases less durable) clothes; new trade policies led to a globalized supply chain. Companies shifted production offshore, where environmental regulations were less stringent, or nonexistent, and garment workers sometimes earned 20 times less than in the U.S. Clothing got massively cheaper.

Forever 21, which initially catered to L.A.’s Korean community, set itself apart by offering a steady flow of new merchandise that capitalized on emerging styles. As it grew, its co-founder Jin Sook Chang reviewed as many as 400 new designs a day. Shopping for fast fashion was exciting—there was always something new, and the merchandise was so cheap that you could easily justify an impulse buy.

While high-end fashion companies were still releasing fall and spring collections, Forever 21’s rival Zara offered fresh styles twice a week. The company, which prefers to distance itself from the “fast fashion” label, says it was just trying to respond to customers’ desires. But stocking inexpensive, ever-changing options also stimulated our desire to buy more. If you found a look you liked at Zara, you had to snap it up right away, or else suffer from fashion FOMO. One study found that, whereas the average shopper visited any given store about four times a year, Zara shoppers stopped in once every three weeks.

Traditional brands initially scoffed at fast fashion, but they also feared losing market share; they, too, began shifting manufacturing overseas and releasing items more frequently. The 2008 financial crisis further cemented fast fashion’s hold on the market. If you were going to a job interview while the economy collapsed around you, a $25 Forever 21 blazer was hard to beat. Even after the economy recovered, people kept buying inexpensive clothes, and in ever-larger quantities. Worldwide, clothing production doubled from 2000 to 2015, while prices dropped: We were spending the same amount on clothes, but getting nearly twice as many items for it. At its peak, in 2015, Forever 21 made $4.4 billion in global sales.

It’s hard to overstate how much and how quickly fast fashion altered our relationship with clothing, conditioning us to believe that our clothes should be cheap, abundant, and new. Trends used to take a year to pass from the runway to the mainstream; now the fashion cycle has become so compressed that it takes just a few weeks, or even less. Americans buy a piece of clothing every five days, on average, and we pay so little for our garments that we’ve come to think of them as disposable. According to a McKinsey study, for every five new garments produced each year, three garments are disposed of.

Like many retail brands, Forever 21 was hit hard by the shift to online shopping. While other companies invested in their e-commerce platforms, Forever 21 doubled down on brick-and-mortar retail, signing leases in malls that were steadily losing foot traffic. When shoppers did visit stores, they found a retailer that was out of touch with the times. In 2015, two-thirds of teenage girls in the U.S. identified as “special size”—plus, petite, tall—but mall shops were slow to respond to this reality. Not all Forever 21 stores had a plus-size section; when the fashion blogger known as Fat Girl Flow visited one that did, in 2016, she found it “tiny [and] dimly lit with yellow lights, no mirrors, and zero accessories on the shelves.”

By contrast, many of the ultra-fast-fashion brands that were arriving on the scene featured thick-thighed models in minidresses and lingerie. PrettyLittleThing has made a point of embracing body positivity—prominently featuring models with stretch marks, models with vitiligo, models with colostomy bags. And while the ultra-fast-fashion companies were partnering with girls like Tricia, as late as 2017 Forever 21 was still spending nearly half its marketing budget on radio ads.

The companies that once shocked the industry with their speed no longer seemed quite so fast. Two decades ago, Zara was revolutionary for offering hundreds of new items a week; nowadays, Asos adds as many as 7,000 new styles to its website over the same period. Fast-fashion companies used to brag about getting a new style up for sale in as little as two weeks. Boohoo can do it in a matter of days.

Boohoo’s profits doubled in 2017. They doubled again in 2018. Meanwhile, the third generation of the Kamani family was making inroads in the fashion business. Umar, Mahmud’s son, had founded PrettyLittleThing when he was 24. Now he was turning it into Boohoo’s splashier little sister. The clothes were bolder (more body-con dresses, more crop tops, more metallics) and the branding was emphatically pinker.

PrettyLittleThing’s branding reflects Umar’s flashy persona. On Instagram, where he has 1 million followers, he’s posted photos of himself posing with Drake, sunbathing in the Maldives, and Jet Skiing behind a yacht. He hosted J.Lo’s 50th birthday party at Gloria Estefan’s house, and claims to FaceTime with will.i.am nearly every day.

The first generation of fast-fashion brands still tends to take its cues from traditional gatekeepers. Ultra-fast-fashion companies more often look to celebrity culture. Sometimes, this takes the form of partnerships: PLT has produced lines with Kourtney Kardashian; Fashion Nova has linked up with Cardi B. Other times, though, ultra-fast-fashion companies simply copy the looks of these and other stars. In 2019, Kim Kardashian posted a picture of herself in her closet wearing a tight gold dress with a midriff cutout. “Fast fashion brands, can you please wait until I wear this in real life before you knock it off?” she pleaded in the caption. Within hours, one company, Missguided, posted an extremely similar outfit on its Instagram page, promising to have the dress for sale within a few days. (Kardashian sued the company for copying her looks and was granted $2.7 million in damages.)

PLT’s aesthetic may be as celebrity-obsessed as its founder, but the real force behind its social-media marketing are the thousands of Bachelor contestants, TikTokers, Instagram models, and YouTubers like Tricia who have been enlisted to post about the brand. Studies show that the more we use social media, the more time and money we spend shopping online. Following influencers correlates with even more shopping. In 2017, data from the social-media-analytics company Hitwise showed that PLT was the most popular emerging fast-fashion brand, with a 663 percent rise in traffic to its online store since 2014. From 2016 to 2019, the company’s annual sales went from about $23 million to nearly $510 million.

Still, in training consumers to look for the shiniest, newest style, companies like PrettyLittleThing might be establishing the conditions for their own obsolescence. Today’s young shoppers have little brand loyalty. Consider Nasty Gal, which was once heralded as the “fastest growing retailer” of 2012 by Inc. magazine. Within a few years it filed for bankruptcy—and was bought by the Boohoo Group, which cut prices and closed the brand’s remaining brick-and-mortar stores. “Pre-COVID, not only were consumers buying and wearing things for a shorter amount of time, but they were also constantly looking for newness, which had been accelerating the cycle by which individual brands come in and out of favor,” says Adheer Bahulkar, a partner and retail specialist at the global consulting firm Kearney. “The sheer amount of newness in the market makes it difficult for any given brand to keep up.”

About two miles away from PrettyLittleThing’s showroom, a line formed outside another West Hollywood storefront. The occasion was the annual sample sale at Dolls Kill, a mass-market brand dedicated to selling nonconformism. On the surface, Dolls Kill looks like the polar opposite of PrettyLittleThing; whereas PLT is all about converging on the trends of the moment, Dolls Kill shoppers identify as misfits and dress accordingly. But the companies are banking on similar strategies to keep young shoppers coming back: aggressive online engagement, an abundance of styles, and unrelenting newness.

Dolls Kill is where you go when you want to buy neon platform combat boots or a pair of shimmery, iridescent bell-bottoms. There’s a dash of mall-goth in its aesthetic, alongside some anime-inspired hyperfemininity and raver psychedelia. Despite—or perhaps because of—its outsider cachet, Dolls Kill has attracted attention from powerful venture-capital investors. Amy Sun, then a partner at Sequoia Capital, a major Dolls Kill investor, surveyed the hundreds of shoppers clamoring to get inside the sample sale: their Billie Eilish neon-streaked hair, their skeleton-print hoodies. From inside the store, club music pulsed hypnotically. “You can feel the brand magic,” Sun said. “Which is super hard to build.”

Dolls Kill’s founders, Shaudi Lynn and Bobby Farahi, met at a rave. She was a DJ; he had recently sold his media company and was “partying,” he later told Inc. Farahi was impressed with Lynn’s fashion sense, and business acumen. She would buy something cute on eBay for $5, then turn around and sell it for $100. “She looked for items that were hard to find, that were viral in nature—items that made people say, ‘Hey, where did you get that?’ ” Farahi said. Lynn and Farahi began dating, and launched an online boutique in 2012. Lynn chose the name Dolls Kill because she liked the way the two words sounded together—one soft, one hard.

At first, they imagined that Dolls Kill would be a niche brand, popular mostly with club kids. But then something started to shift—the Burning Man aesthetic was creeping into the workaday world; festival culture went mainstream. Word began to circulate: If you wanted your #ootd to be colorful and weird and stand out on social media, Dolls Kill was a good place to shop.

In the age of the fickle consumer, one strategy is to make customers feel like part of a community. Dolls Kill proved adept at this. “All the models on our sites are customers who submitted photos of themselves. They are just ecstatic, and they become evangelists,” Farahi has said. In 2018, the company opened its flagship Los Angeles store. It was designed to look like an industrial nightclub, with raw-concrete floors, exposed-brick walls, and an Italian sound system the company referred to in a press release as “insane.” The stores are less a revenue generator than a way to reinforce that feeling of community, Farahi told me: “Are they here to shop, or are they here to meet other people, hang out, be part of a movement?”

In 2014, Dolls Kill attracted $5 million in an initial round of funding led by Maveron, the venture-capital firm co-founded by former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz; five years later, the company raised another $40 million in a second round. That round was headed by Sequoia, which thinks Dolls Kill has the potential to be a “generation defining” brand, Sun told me. Rebellion against the mass market had mass-market appeal, she believed. “The age of conformity is over,” she said. “Anytime I wear anything from them, people are like, where did you get that?”

Despite its aggressive attitude, Dolls Kill has its own network of influencers and brand ambassadors, just as its more conformist peers do. The first day of the sample sale was invitation-only; the room was full of Dolls Kill superfans, but also influencers like Jake Fleming, a lithe, blond fashion YouTuber in his early 20s. He told me that he liked Dolls Kill just fine—its clothes photographed well and he always wore them to Coachella—but attending this event was basically work for him. “We went to a brand party before this, and we have two more brand parties tomorrow,” he said, a hint of fatigue evident in his voice.

The Dolls Kill sample sale was one of the last times I was in a crowded room. A month later, when most of the country shut down, I spent many hours scrolling through online stores—not so much buying but browsing. PrettyLittleThing had hundreds of leggings listed on its website, and I looked at all of them: white faux leather, flame-print mesh, seamless gray ombré. Dolls Kill was featuring velour tracksuits in candy-colored tones. The browsing suited my mood of low-key dissatisfaction, the itchy, procrastination-prone state that one of my friends calls “snacky.” I had a closet full of clothes and nowhere to wear them, but I added items to my basket anyway—improbable outfits for imaginary parties in a world that no longer existed.

The ultra-fast-fashion brands have designed a shopping experience that makes the consumer feel as if the clothes magically appear out of nowhere, with easy purchasing and near-immediate delivery. The frictionless transactions contribute to the sense that the products themselves are ephemeral—easy come, easy go.

Of course, the clothes don’t come from nowhere. Ultra-fast fashion brings with it steep environmental costs. “You may get a $1 bikini,” Dana Thomas, the author of the 2019 book Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes, told me. “But it’s costing society a lot. We’re paying for all of this in different ways.”

Producing clothing at this scale and speed requires expending enormous amounts of natural resources. Cotton is a thirsty crop; according to Tatiana Schlossberg, the author of Inconspicuous Consumption: The Environmental Impact You Don’t Know You Have (2019), producing a pound of it can require 100 times more water than producing a pound of tomatoes. But synthetic textiles have their own problems, environmentally speaking. They’re a major source of the microplastics that clog our waterways and make their way into our seafood. McKinsey has estimated that the fashion industry is responsible for 4 percent of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions; the United Nations says it accounts for 20 percent of global wastewater.

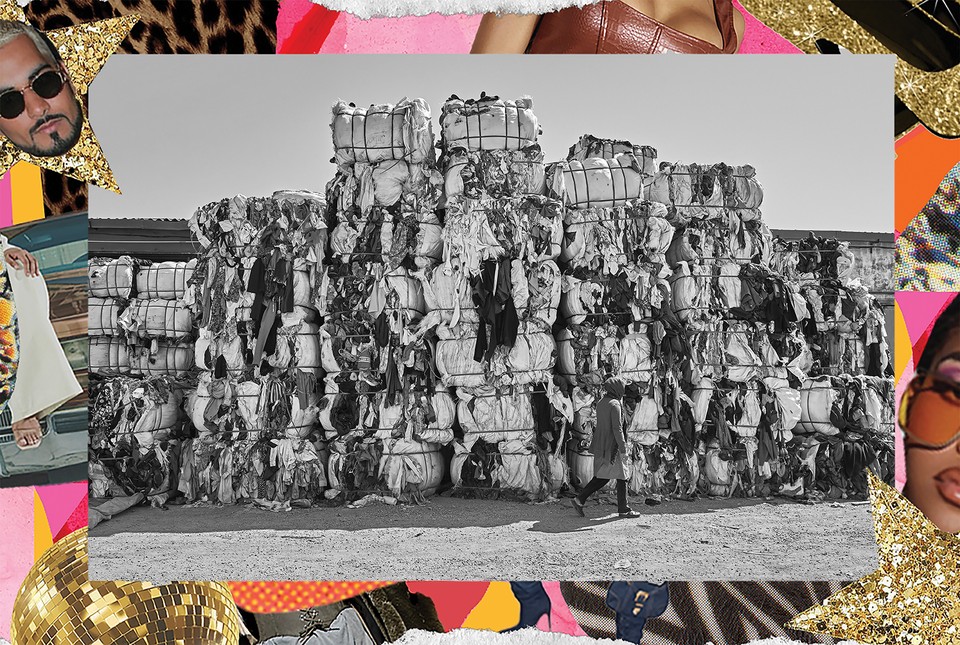

Meanwhile, the volume of clothes Americans throw away has doubled over the past 20 years. We each generate about 75 pounds of textile waste a year, an increase of more than 750 percent since 1960. Some thrift shops, glutted with flimsy, synthetic wares, have stopped accepting fast-fashion donations. Discarded clothes get shipped overseas. Last year, a mountain of cast-off clothing outside the Ghanaian capital city of Accra generated so much methane that it exploded; months later, it was still smoldering.

Fast-fashion companies tell their customers that it’s possible to buy their products and still have a clean conscience. H&M has ramped up its use of organic cotton and sustainably sourced materials; Boohoo sells 40 or so items partially made from recycled textiles. Aja Barber, the fashion-sustainability consultant, told me she sees most of these efforts as little more than greenwashing: “It’s like, ‘Oh look, these five items that we made are sustainable, but the rest of the 2,000 items on our website are not,’ ” she said.

Then there is the human toll. The rise of fast fashion was made possible by the offshoring of manufacturing to countries where labor costs are kept low through the systematic exploitation of workers. When Rana Plaza, an eight-story factory in Bangladesh, collapsed in April 2013, killing more than 1,110 and wounding thousands more, the disaster brought international attention to the alarming labor conditions in overseas garment factories. Some ultra-fast-fashion companies have emphasized on- and near-shoring, relocating manufacturing domestically or to nearby countries, which allows them to speed up production and distribution. About half of Boohoo’s merchandise is produced in the U.K.; in 2018, 80 percent of Fashion Nova’s clothes were reportedly made in the United States.

But domestic manufacturing doesn’t necessarily mean ethical manufacturing. Several of Fashion Nova’s Los Angeles–based suppliers were investigated by the Department of Labor for paying wages as low as $2.77 an hour. (Fashion Nova now mandates that all contractors and subcontractors pay minimum wage.) Reporters in the U.K. have uncovered disturbing practices at Boohoo’s suppliers, including impossible quotas, unsafe working conditions, and garment workers paid well below the minimum wage. Fast-fashion companies typically outsource production to a long chain of contractors and subcontractors, making accountability a challenge. Eventually, Tricia started shooting Shein haul videos again, after the company posted a self-exonerating explication of its labor practices on its website. But fast-fashion influencers, like fast-fashion consumers, have little insight into supply chains that are kept intentionally opaque.

Last spring, as the coronavirus tore across Europe, Boohoo and other fast-fashion brands kept distribution centers open. Workers told labor advocates that social distancing was impossible, and that they were expected to bring their own hand sanitizer. By late June, Leicester, the U.K.’s textile-manufacturing hub, had an infection rate three times higher than that of any other city in the country. (Boohoo has since pledged to make its supply chains public and require third-party suppliers to adhere to ethical guidelines.)

Regulators have started to take notice of fast fashion’s less savory practices, though their efforts have failed to keep pace with the industry, or have just plain failed. In the U.K., a special parliamentary committee that spent a year studying the environmental and labor impact of fast fashion made a number of recommendations, including levying a one-penny garment tax that would be used to improve textile recycling; the government rejected them all. Last fall, the California state assembly failed to pass a bill that would have held fashion companies accountable for wage theft by third-party contractors.

Also last fall, an independent audit commissioned by Boohoo found that the company had been quick to capitalize on COVID‑19 as an opportunity to boost sales, but had paid little attention to low wages and unsafe working conditions in its suppliers’ factories both during the pandemic and prior to it. “Growth and profit were prioritized to the extent that the company lost sight of other issues,” the report found. But it also concluded that Boohoo hadn’t broken any laws. The day the report was released, the company’s stock rose 21 percent.

For the moment, at least, there seems to be insufficient political will to rein in the industry’s excesses. But that doesn’t necessarily mean ultra-fast fashion is here to stay. With so many cheap products saturating our feeds, perhaps buying yet another disposable bodysuit or bandeau won’t feel as stimulating as it used to.

The last time I spoke with Tricia, she had enrolled in a premed program. She told me that she’d been making a new kind of video. “I’m styling the clothes I already have in my closet—so I’m keeping up with fashion, but using the clothes I already have,” she said. Haul videos were still popular, but she thought I should be paying attention to another trend: “Secondhand clothing and thrifting is so hot right now.”

This article appears in the March 2021 print edition with the headline “Ultra-fast Fashion Is Eating the World.”

*Lead image credits: Illustration by Barbara Rego; images from PrettyLittleThing; Barbara Rego; FreePNGImg; CleanPNG; Clipart Library; Space Frontiers / Heiko Junge / Getty; Shutterstock

https://ift.tt/3aJgYNH

Fashion

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "PrettyLittleThing, Shein, ASOS, and the Rise of Ultra-fast Fashion - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment