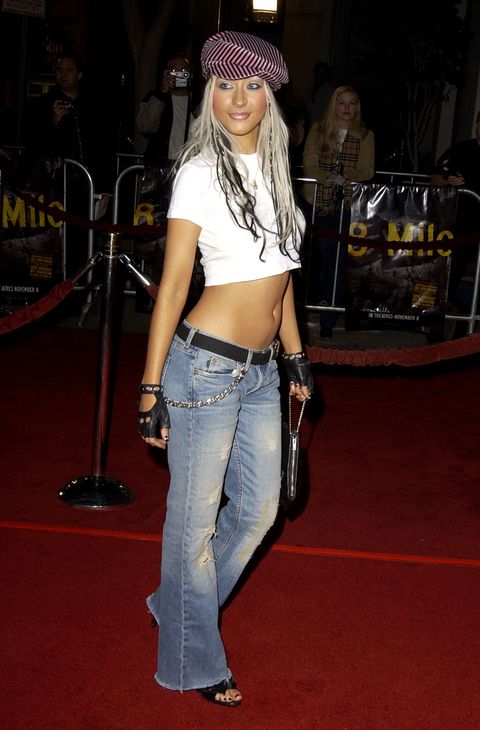

Bennifer has reemerged, there’s a new Sex and the City, and the girls are wearing low-rise jeans again. It’s official: the '90s are out, and the noughties are in. And Gen Z can’t get enough. Videos tagged “#Y2KAesthetic” and “#Y2Kfashion” on TikTok have a collective 405 million views and counting. The trend has spurned some intense conversations over the past few weeks and triggered feelings for elder millennials. One Twitter user expressed her frustrations in a Twitter thread.

“Seeing everyone dress in 2000s fashion for fun or trend actually triggers a lot of body image issues and eating disorders for me and I know it’s not anyone’s fault but I wish ppl understood the height of fatphobia within that era of fashion was probably the worst in history,” she wrote.

Recent Y2K fashion discourse is missing some salient points, namely, any reference to women of color—or how the toxic combination of fatphobic media, fashion trends, and emerging social media channels created the perfect storm. Rather than let this be another divisive talking point in the millennials vs. Gen Z culture wars, let’s have an honest conversation.

Fatphobia wasn’t invented in 2001, but one could easily argue that a rise in Internet access played a pivotal role in Y2K’s hyper-toxic culture. Only 22.9 percent of U.S. households had a personal computer in 1993. By 2003, the same year Fox premiered The Simple Life, starring blonde thinspo heiresses Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie, 61.8 percent had one.

Early social media networks, like LiveJournal, Myspace, and Tumblr, quickly gained popularity among the adolescent set, and those looking to stay thin by any means necessary. “When I think about the 2000s, I think about LiveJournal communities and Tumblr accounts that were very pro-ana (anorexia nervosa),” Fashionista Editor-in-Chief Tyler McCall says. But even if social media hadn’t started to take off in the early aughts, traditional media channels made it clear: Thin was in.

The fashion industry played an integral role. For YouTuber Angela Benedict, who was an aspiring actress in her early 20s, the clothes were shrinking, “I hadn’t gained any weight. Why am I looking this way? Why is my stomach spilling over? Why are my hips protruding? It's like the clothing was built in a way that made your body look distorted.” Benedict recently shared her experience with disordered eating in a video titled "Y2K Gave Me an Eating Disorder."

Reflecting on these unforgiving fashion trends makes one wonder about the idolatry of youth in fashion. The average age for models entering the industry in 2011 was between 13 and 16 years old. The models were pubescent, but the clothing they were modeling was being marketed and sold to adult women, who in turn internalized the message being sent. “You either thrifted, made your clothing, or there was the option a lot of us took—change yourself to fit the clothes,” Benedict says. It took her years to come to terms with her body dysmorphia. It wasn’t until last year, when she turned 40, that Benedict even realized she had an eating disorder.

Y2k fashion trends—with their emphasis on low-rise jeans; exposed thongs; and baby tees—were understood to celebrate a very specific body type, one generally found in teenaged girls. The trends helped normalize the sexualization of pubescent girls. Young women internalized this message, unknowingly embarking on a lifelong pursuit of youth and thinness, never stopping to critically assess the unrealistic body standards.

The media furthered that message by consistently pushing thin, white fashionistas as the standard of beauty. The same year Mary-Kate Olsen entered rehab for an unspecified eating disorder, she was on no less than four major magazine covers.

But if you were too thin, then it was a problem. U.K. tabloid The Daily Mirror printed the following about actress Keira Knightley in a 2009 article: “The naturally slender actress looked painfully thin in a purple strapless confection, her protruding collarbone more pronounced than ever.” This is the same outlet that two years earlier published an article urging “hot, thin women” to have a fat friend so they’d look better. Hypocritical? Yes. Effective? Unfortunately, also yes. There was a spike in eating disorder diagnoses between 2000 and 2009, with teenage girls making up the lion’s share of patients.

While the media’s depiction of white women during this time was problematic, we cannot ignore how women of color were treated: We were either fat or nonexistent.

It’s almost unbelievable now, but in 2005’s Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, America Ferrera was the fat friend. Ferrera, who is Honduran, looked like so many Black and Latinx girls in my life. Ditto for America's Next Top Model alum Toccara Jones, who was singled out as a plus-sized model. Even Beyoncé (who coined the term bootylicious in 2002) couldn’t escape it; a 2009 NBC.com story headline reads, “Beyoncé's Rep: She Is Not Fat,” and she wasn’t.

There’s a lot to be said about the lack of discourse around our Y2K experiences with body image. This is an extension of the idea that women of color don’t have these issues. Some academic studies prevalent at the time stated that Black girls and women were more satisfied with their bodies than their white counterparts. The predominantly white media took that to mean that these issues didn’t exist for us. But they did, and early-2000s Black media was just as problematic. Look at Moesha; after the iconic show was picked up by Netflix last year, viewers were shocked by blatant fatphobia, mostly thrown at Moesha’s friend Kim Parker, played by actress Countess Vaughn.

No discussion about Black women’s body image issues in the early 2000s would be complete without discussing the video vixen (as New Yorker writer Doreen St. Félix pointed out). “Urban” media, including magazines like King and XXL, as well as music videos and movies geared toward Black audiences, peddled a specific look. Women had narrow waists and flat stomachs, but large butts, hips, and thighs.

Much like their white counterparts, urban fashion brands reinforced this body standard. Popular brands like Baby Phat, Sean John, Rocawear, and the aptly named Apple Bottoms used the same advertising models. Popular music videos of the artists behind these brands Sean “P. Diddy'' Combs, Jay-Z, and Nelly had women with the aforementioned look ostensibly outfitted in their brands. Those of us who were teenaged girls then wanted the clothing and the bodies to go along with it.

One Twitter user summarized it perfectly, admitting to “using white girl ED habits” to achieve the optimal video vixen body. Just because women of color's impossible standards weren’t model thin and blonde, it doesn’t mean we don’t also have baggage.

A lot of commentary around this topic seems to be in defense of millennial women’s feelings, but I don’t think that’s necessary. We’re in a much different place than we were in the early 2000s; to McCall, that’s a good thing. “I think because [Gen Z has] grown up in this environment of body positivity, it’s different,” she shares. “I think growing up in a media that says you can have plus-size models on runways or fat influencers that it doesn't feel the same to them.”

The optimist in me would like to agree. I hope that the last decade of body positivity provides some sort of protection, a digital talisman, of sorts. If it doesn’t, I hope that Gen Z at least feels comfortable enough to turn to their elders for guidance, or just someone to listen to.

As a millennial woman still reckoning with the aftermath of Y2k body discourse, I say to them: Wear your low-rise jeans, girlies; it’s your time to shine. All I ask is that you honor your body, love yourself, and, please, don’t bring back layered polo shirts; none of us can survive that.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Article From & Read More ( Y2K Fashion is Back. Are Its Bad Vibes Back, Too? - HarpersBAZAAR.com )https://ift.tt/3eITuLn

Fashion

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Y2K Fashion is Back. Are Its Bad Vibes Back, Too? - HarpersBAZAAR.com"

Post a Comment