In the late summer of 1986, I packed up my things and, with my 1-year-old son, moved to Detroit to begin writing about fashion for the News. I was 30, and I remember thinking that the true fashion of America was vernacular. It was the plain cotton dress, the beauty of the useful garment or the secondhand shirt. But, equally, it was the extraordinary loose-hip drape of the jeans of a young Detroit designer named Maurice Malone, who was involved in the city’s burgeoning techno scene, and who was the first designer I knew to see that the look of falling-down trousers on skinny male bodies was a kind of aesthetic. Proust may have written knowingly of women’s dress, but it was James Agee who showed me, in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, his and Walker Evans’s portrait of three tenant farming families in Depression-era Alabama, that all clothes “shaped to their context” can have dignity — the tailored suit as well as a “pierced, sewn-together cockeyed” sun hat. Or it was F. Scott Fitzgerald, writing about the early flappers, who led me to believe that the real archetype of the emancipated woman was not Coco Chanel, as historians maintain; rather, it was a hard-boiled American teen in a flimsy dress. Later, when I found a photograph of a young flapper in a cheap cotton shift, her bare legs dangling over the side of a Model T, I finally understood what Fitzgerald meant when he wrote, “Isolated during the European War, we had begun combing the unknown South and West for folkways and pastimes.” He was describing how the freedom of the automobile had allowed for new freedoms among young people, which gave rise to a liberated homegrown style. “Who could tell us any longer what was fashionable and what was fun?” he asked.

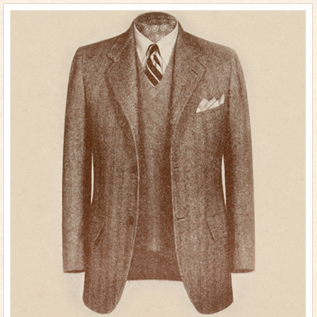

Of course, the roots of America’s greatest contribution to fashion — the jaunty, practical, ready-to-wear style known as sportswear — are precisely in the cheap and the uninhibited: the common housedress, the nylon nightie, the calico shirt, the heavy cotton double-topstitched chore jacket. Take, for example, the designer Claire McCardell, who in the 1930s and ’40s translated many of these ordinary garments into fashion. As Sally Kirkland, a fashion editor for Life, put it, “Claire’s girls were padless, braless, and heel-less.” (The prices were also startling: McCardell’s Popover dress, first issued in 1943 and based on a housedress, sold for $6.95.)

The American vernacular is one of the most powerful styles that there is, running through the visual arts, music, literature, and architecture. It may go in and out of popularity, but it can always be reactivated by an individual artist, designer, or craftsperson. That’s what I thought in 1986. And it’s why I didn’t buy into the notion that American fashion played second fiddle to European fashion. All around me I saw ingredients for a way to dress that was phenomenally rich. And entirely our own.

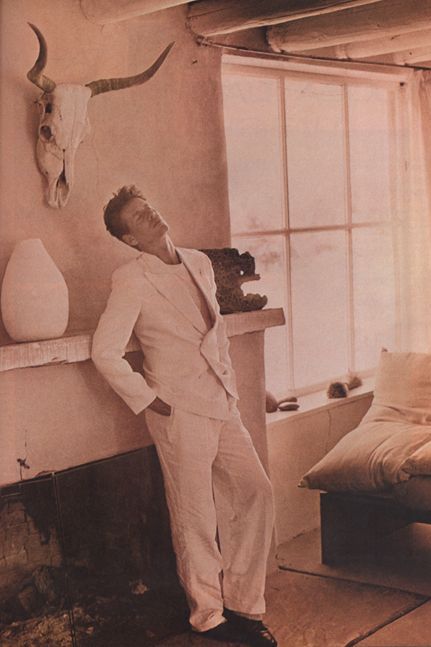

In 1986, when I got to Detroit, having met the job’s basic requirements as spelled out in the ad — “good writer, no fashion experience necessary” — the clothes on New York’s runways were definitely not simple and unpretentious. Fashion is meant to reflect the moment, and the city was having a moment of excess. It was the era of the ladies who lunch, of the Wall Street fat cat in the form of corporate raiders and junk-bond kings, and a front row stuffed with retail bosses. Underlying many collections was a sense of competition, felt in everything from the lavish amounts of French embroidery to Donna Karan’s vision of a cashmere-draped executive. Not everything looked so complicated. The designer Zoran (who once said, “You cannot spend ten days making a dress”) pioneered a concept of minimalist sportswear, done in high-quality fabrics and a handful of solid colors, which won him a huge following in both the U.S. and Europe. And for Calvin Klein’s 1984 menswear campaign, the photographer Bruce Weber made sepia-toned portraits of the designer at Georgia O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch in New Mexico — an attempt to relate Klein’s own feelings about comfort and neutral tones to a uniquely American landscape. Still, I wanted more. I wanted designers to get out of the New York bubble and to see what I saw in the “unknown” parts of the country — the old factories, open spaces, towns, people who have an aesthetic of their own. And I wanted them to extract from that a new American vernacular. As a reporter who had traveled around a bit, I believed it was possible to discover these things, if one looked.

The problem is I didn’t look, at least not in any meaningful way. Instead, I got swept up in covering the industry. Not that this was entirely a waste of time: I got to experience the thrill of seeing the collections of Martin Margiela, a great abstracter of ordinary things (trash bags, wigs); the arresting realism of Helmut Lang; the complex femininity of Miuccia Prada. But by the end of the ’90s, the story had fully shifted to Europe and the battles between LVMH and Gucci Group (now Kering) for control of the legendary fashion houses. I witnessed the rise of corporate-managed “luxury” and the standardizing of tastes through the spread of similar expensive branded products — what the historian Olivier Saillard calls “the empire of luxe.” Fashion has always been ridiculous and snobbish. But only in the past 20 years has it been stuck with the gold-plated handle of luxury, the sine qua non of banality. By the late 2010s, the general view was that New York Fashion Week had become largely irrelevant, a slog of uninteresting shows interspersed with a few reliable big names. The Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) is partly to blame. But it was also exacerbated by the likes of Anna Wintour and department-store buyers who pushed young designers down the chute of luxury by encouraging costly runway shows and editorial-looking “statements,” only to wind up with a kind of visual consensus: Too many collections looked the same.

All these changes, combined with the ballooning size of the presentations, made me feel that I was on a treadmill, tied to this whirring mechanism — “the fashion system.” It would be a couple of decades or more before I focused again on the things I wanted to see. And now it was more urgent than ever.

Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge of the Met’s Costume Institute, which houses the galleries of the Anna Wintour Costume Center, believes a renaissance of American fashion is under way. That assertion may seem self-serving, since he has organized “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion,” the museum’s first exhibit devoted to American dress in 23 years, which opens on September 18.

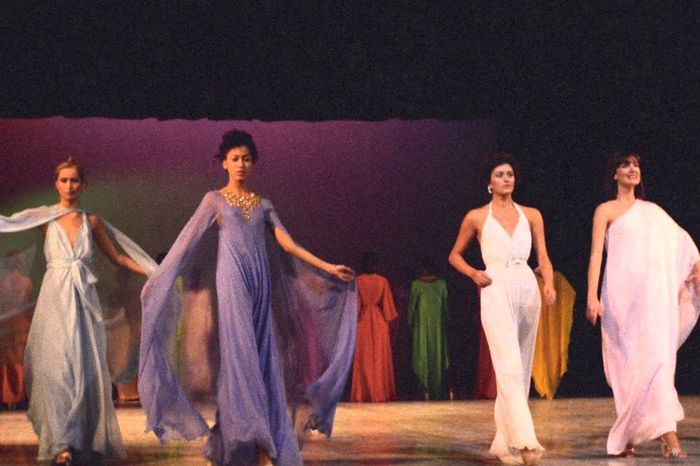

Initially, Bolton set out to do an exhibit in conjunction with the Met’s American period rooms, one that would attempt to tell unknown stories of the past and align them with men’s and women’s historical dress. It would allow curators to address the issue of slavery, since some decorative objects — fine mahogany paneling, for example — were made by enslaved people. (As the historians Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace have pointed out, New York’s booming garment trade in the 1840s and ’50s was partly owed to the expansion of southern slavery and the demand for cheap clothing like dungarees and flannel shirts.) That exhibit, to be staged in the American Wing, will still go on next May, and its fashion will span the mid-1800s to the present. (Originally, the idea was to end in 1973 with the Battle of Versailles, when five American designers met five Paris couturiers in a fashion show that made the French look old hat and the Americans frisky and modern, in large part thanks to sportswear.)

But all that planning was before COVID, the murder of George Floyd, and the protests and institutional reckonings that followed. So Bolton decided to turn “In America” into a two-part survey, with fashion in the first part drawn from the 1930s up to the present. “That part very much came out of Black Lives Matter and COVID,” he says. “It was me looking at younger designers and the conversations they were engaging in: racial diversity, body inclusivity, gender fluidity, sustainability.”

The Met, like the wider fashion community, is confronting its own history of racism and narrative exclusion. In 1998, the Costume Institute chose to honor the pioneers of American sportswear in an exhibit that spanned 1930 to 1970. Recently, I read the catalogue of that exhibit, and while I didn’t expect to see nonwhite designers represented, it was apparent that no one had felt the need even to acknowledge or explain their absence — it was taken for granted. So this upcoming exhibit is a chance for the Costume Institute to address the monochromatic interpretation of American fashion it had reinforced for decades: that it largely revolved around big sportswear and lifestyle brands, with little representation of racial or gender diversity and little space for talent with simply brilliant ideas. Fully half of the designers in the show are contemporary, including Telfar Clemens, Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss, Emily Adams Bode, and many who no doubt would have been unrepresented, and unlikely to get a seat at the Met Gala, in the past. The clothes will be displayed in a grid based on a patchwork quilt.

The mission to be more pluralistic is worthy, but “In America” is likely to strike some people as knee-jerky and overly careful. One of the first designs visitors will see is a white sari-inspired dress by Prabal Gurung, with a beauty-pageant sash that reads WHO GETS TO BE AMERICAN? Is the piece an earnest plea on behalf of threatened minorities from a man who is himself an immigrant, or is it pure clickbait? Surely it is both, given the importance of social media. (Instagram is the exhibit’s main sponsor.) And with so many themes to stitch together, from identity to community to zero waste, there’s a danger the quilt won’t cover anything satisfactorily. To represent the work of Christopher John Rogers, who is Black and originally from Baton Rouge, Bolton chose a plaid magenta evening gown with an extravagantly full skirt. In a teaser video to highlight the exhibit, Bolton drew a comparison between Rogers and the couturier Charles James, an American master of mid-century splendor. Yet this seems an odd throwback line and curatorial choice, given the remarkable progress Rogers has made recently. At 27, he has developed into one of the best sportswear designers we’ve seen in years, with tailoring and separates that finely balance realism and exaggeration. And it’s ironic that at a moment when Bolton wants to stress a different way of understanding American fashion, centered on politics and identity, he is overlooking Rogers’s actual achievement. Rogers credits the change in his work to having more time to design, a consequence of the lockdown as well as of his decision to not show on the NYFW timetable. He will present later.

In one way or another, American fashion has always embraced offness, otherness, queerness, outsiderness. But in a society as class-riven and segregated as ours, it is only in recent years that otherness has truly come to the fore. Social media has just accelerated that process. This seems to be the renaissance that Bolton is pointing to: the emergence of a socially conscious group of designers who want to do things on their terms. But based on the bits of the Met exhibit that have been released, there still lingers a myopia around the question of what American fashion is. In the past, it was about sportswear, couturiers with a strong artistic eye like James. Now, in a strange way, we have gotten pulled far in the direction of inclusivity and political correctness but without much thoughtful consideration. And there is a danger that we will just end up swapping one rhetoric for another — the language of luxury for the language of politics and identity.

I did see one sign of a renaissance, however. It’s a piece called “Veil Flag,” and it’s by the artist Sterling Ruby, who two years ago started a couture clothing line, S.R. Studio. LA. CA. He shot a video for the Costume Institute of a black-washed denim wrap slowly being unfurled by a Black man to reveal an American flag whose details have been all but erased. Conceived near the end of the Trump presidency, it is a garment compact of dignity and sadness, executed with vernacular precision, and it’s no wonder it will be displayed prominently in both parts of the exhibit.

There is an irony to calling this moment a renaissance. Much of the system that once supported daring new talent, and justified the cost of a show, has vanished. New York, which used to be home to many department stores and celebrated specialty stores, has had its retail identity hollowed out. Barneys, Jeffrey, and Linda Dresner are some of the better stores that have closed in the past few years. This is a loss not just for shoppers but for the eco-system at large: As the historian Caroline Rennolds Milbank has noted, much of the influence in New York collections in the 1960s — the fascination with peasant blouses, patchwork, bold prints — came from youthful boutiques like Teeny Weeny and Paraphernalia. “Although the couture is sometimes described as a laboratory for fashion,” Milbank wrote in her book, New York Fashion “1960s boutiques were actual laboratories.”

Yet the closing of retail outlets and the challenges of COVID have forced young designers to adapt to new systems of delivery and distribution: They’ve become so nimble at reaching their customers through apps and drops. At the same time, their sensibilities are rooted in values that appeal to today’s consumers, such as sustainability or body inclusivity. That balance of skills has relieved many of them, I think, of the pressures of showing at Fashion Week, being in magazines, making “editorial” clothes just to please an editor or a buyer. They have realized that they don’t need any of it.

Still, it raises an interesting question, says Justin Kern, who, with his partner, Stephanie Danan, owns the Los Angeles label CO. “What is American fashion if you actually don’t have to do any of the stuff you’re supposed to do?”

I think the answer is clear: It is the small, independent labels with an autonomous drive, which, if you look carefully, are expanding the notion of vernacular to include other cultures and sensibilities. This is true of Rio Uribe, the designer behind Gypsy Sport, who has collapsed many assumptions about sexuality and gender, resulting in an ornery, stripped-down aesthetic. He has also been innovative with salvaged objects, including his grandmother’s crocheted doilies. And it’s true of the designers Zoe Latta and Mike Eckhaus of Eckhaus Latta. From the start, their clothes have been insistently anti-luxury, grounded in plain, democratic sportswear. Their knits and denim are often praised as “homespun” and “hand-crafted,” but maybe a truer term for the effect is unworked.

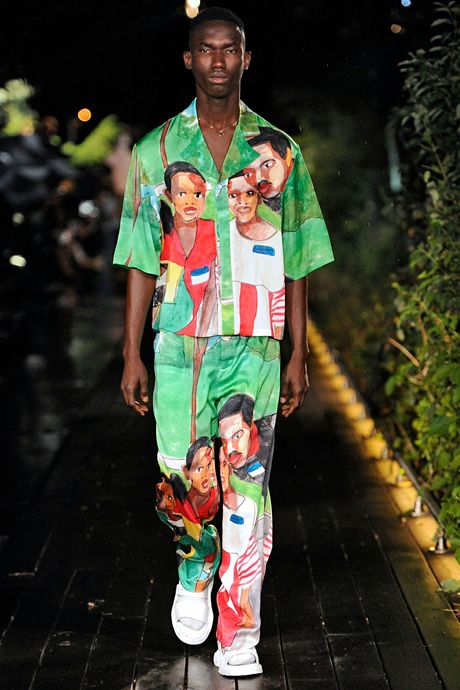

But as someone who loves the vernacular, who has been guided by the polestar of a delinquent-looking flapper all these years, who believes in her share of the American fashion story and who has searched for new expressions of it, I can tell you that you can look at something without seeing it at all. Three years ago, Kerby Jean-Raymond staged a show at the Weeksville Heritage Center, an early Black settlement in Brooklyn. That same season, much of the attention was on a show at Calvin Klein in which Raf Simons used a theme of American horror — with, among other styles, scuba dresses featuring the famous still from Jaws. Jean-Raymond, meanwhile, showed a group of casual dresses and shirts with colorful, hand-painted images of Black families at cookouts or holding babies — as he put it, “just Black people doing normal things.” Jean-Raymond’s view was something new. There have been influential Black-owned streetwear brands, and Sean Combs’s early glammed-up extravaganzas, but when in the history of American fashion have Black families “doing normal things” been the focus? I can’t think of one instance. But at the time, I didn’t see the significance.

Others are literally taking their cues from the land. Eighteen months ago, Kern and Danan of CO decided to start a line of climate-beneficial clothing, an addition to their main label, which is now ten years old. “We’re this California label. We’ve done a lot with architecture and things that are specific to the West Coast,” said Kern. “A resource we have here is agriculture. Is there a way to tap into that?” The result of that thinking is Natural World: a small-batch collection primarily grown and made within the state. The wool, which feels like cashmere, comes from sheep in Solano County; it was woven at Huston Textiles, near Sacramento, on vintage industrial looms. Next season, Kern and Danan plan to work with a cotton grower who is breeding seeds that naturally produce color, no dyes needed.

“The CFDA doesn’t call us,” Kern said. “We’ve never met them. It’s still so geared toward New York and Europe, and I feel they are missing out on what’s happening in the west, from ag to tech, that are really going to be the future of this industry.”

This summer, I drove across the United States with my son, who is now 35. Because of the smoke from the wildfires in the West, we did not see clear skies until the western side of the Sierras, some 3,000 miles into our journey. Driving from the East Coast to Los Angeles, you quickly become aware of the sameness of things — the same restaurant chains, the same Targets — and the vanishing culture of towns and mills and storefronts that Walker Evans throughout his life documented. But you never know where the treasures lie, where the world begins again. Next week, when I hit the shows, one designer I’ll be going to see is Elena Velez. She is 26, a native of Milwaukee with a degree from London’s Central Saint Martins, and her deconstructed dresses — often wisps of repurposed sailcloth and scrap metal — look at once delicate and aggressive. Her favorite inspiration is, of all things, the old factories and trades of the American Rust Belt.

More From fall fashion issue 2021

https://ift.tt/3jvZ06G

Fashion

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "My Endless Search for American Fashion - The Cut"

Post a Comment