Almost two years on, it’s clear that the pandemic ushered in a seismic shift in how we interact with fashion. Since the implementation of lockdowns worldwide, internet shopping has become the most prevalent way that we buy our clothes. In particular, buying and selling pre-loved luxury pieces has become the side hustle du jour. Depops popped and Instagram shops opened their digital doors to a whole new market of youths desperate for a bargain piece of fashion’s past.

In particular, this desire has been driven by the proliferation of ‘archival’ fashion Instagram accounts. Moodboards with runway images of obscure brands from the 1990s screenshotted from Tumblr, or Comme des Garçons campaign imagery nicked from Pinterest, have become one of the most common ways we interact with fashion imagery. And to accompany this growing interest, some savvy people have worked out that you can capitalise on this particular trend.

But a small selection of resellers are experimenting with the format of the shop. They’re treating their businesses like an editorial platform or community-building space, rather than a site simply for commerce. These shops are pushing fashion 'communication' into more interesting areas, much more so than more established shops or fashion brands.

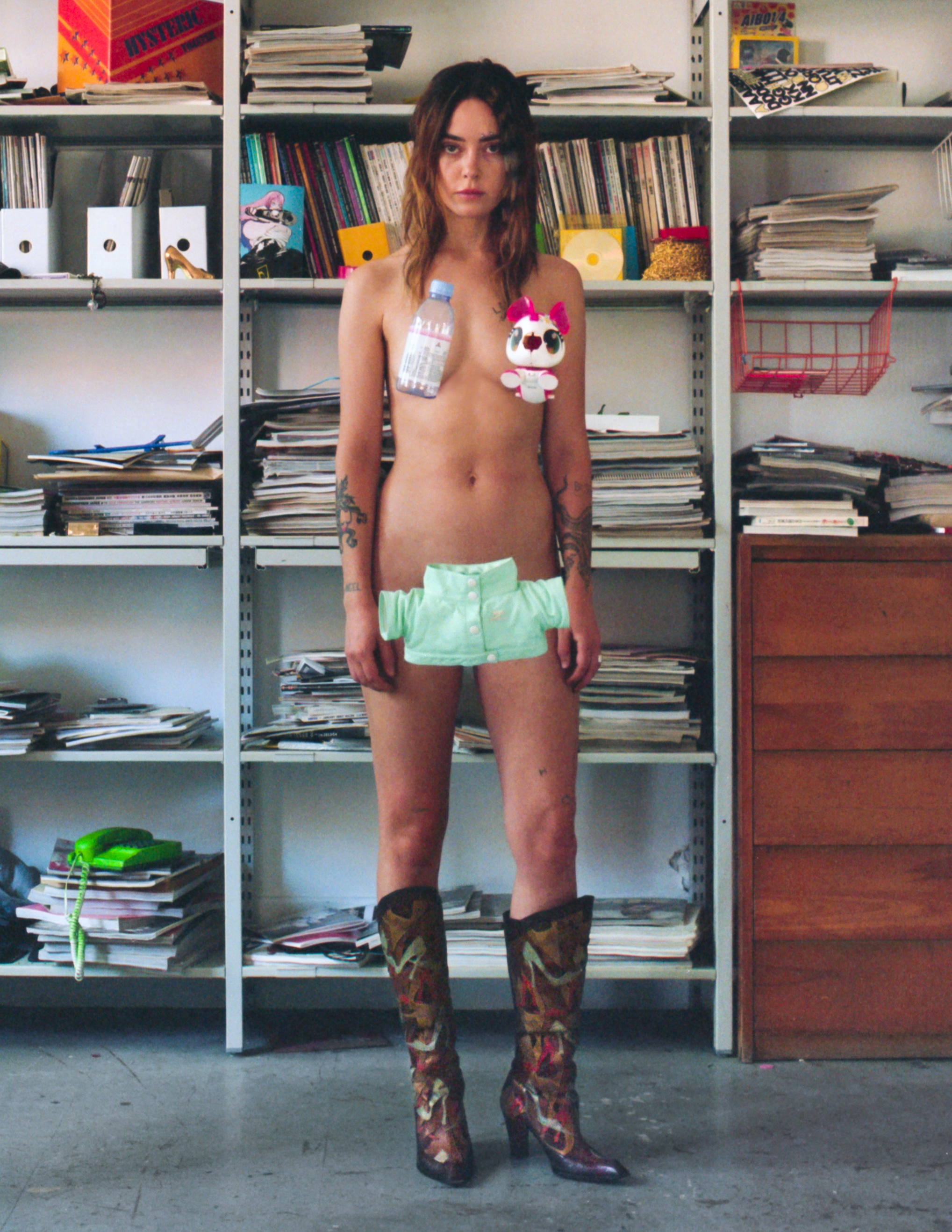

Image courtesy of Galtev

Stylist Mina Galan cites the pandemic as the event which encouraged her to take reselling more seriously. “I was reselling for years, but I was doing it low-key you know, selling on eBay or Depop”, she says. Once lockdown hit, she teamed up with interior designer Emilio Teves to start the webshop Galtev.

The shop sells fashion and homewares side-by-side: 90s Gaultier rubs shoulders with objects from design legends such as Carl Auböck. The ‘look’ is particular — at Galtev, the selection is more about world-building, sharing Mina and Emilio’s aesthetic tastes, than providing for a broad customer base.

Mina explains that being able to have creative control over Galtev is invaluable. “It really started because of the bullshit around having to chase people to do creative stuff and not having a platform for ourselves,” she says. She hopes that they can expand Galtev’s capacity soon, so it can be a platform for more than just selling clothes and objects. “I love the idea of having it merged with other things, like doing our own clothing line”, she continues, “because at the end of the day, it's collaborating with other people that I’m interested in, so why just be a shop?”

Image courtesy of STOF Store

Antwerp-based STOF Store have a similarly expansive approach. Run by Karina Zharmukhambetova and Maude Van Dievoet, STOF specialises in avant garde Belgian design. Their primary aim is to share stories from those who are devout followers of the Belgian brands, such as the subject of their next blog post — a woman who had her wedding dress designed by Walter van Beirendonck.

“These are stories that people would never ever hear if we hadn't gone out and talked to these people”, Maude explains. The motive, they say, is to avoid getting totally sucked into just selling and to bring Belgian fashion enthusiasts together, providing the community with a place to share their stories and collections.

Image courtesy of luckynumber.8

Field Skjellerup, who founded the Instagram shop @luckynumber.8 in 2018, also finds the communitarian aspect of reselling most compelling. “Facilitating conversation and discussion is way more interesting to me,” he explains, “I can think of a few stores where what they stock is insane, but they might as well be a fast fashion store because all they do is pump out clothes”.

Based in Auckland, NZ, Field sells a small selection of pieces by designers you’ve probably never heard of, such as the ura-Harajuku brand Bio-Politics, or short-lived New York label Sandy Dalal Ltd. “I'm quite open-minded as to what I stock, but my main passion is the people that haven't been well rewarded over the years”, Field explains. “I like it when designers only lasted three years”, he continues, “I like the challenge — I feel like something means more to me when I really have to hunt for it”.

“For me personally, the exchange of clothing is actually not the most important thing”, Field explains. Which is why, alongside the shop, Field shares his research both on @luckynumber.8 and through the account @exitscan, sending links to films with a fashion focus to his followers on request, like Takeshi Kitano’s 2002 film Dolls, featuring costumes by Yohji Yamamoto, or Sally Ingleton’s 1997 documentary Mao’s New Suit, which follows two young Beijing-based designers and their efforts to create a new era in Chinese fashion history.

It’s this deep research into ‘archival’ fashion which seems to be the driving element for most, and it’s a pretty shared consensus that Montréal-based stylist and art director Shahan Assadourian started it all off. Growing up in a small town outside Toronto, Shahan felt alienated from the fashion world and was desperately seeking a way in. Back in the early 2010s, Shahan’s primary interactions with fashion were through old copies of the runway photo biannual Gap Press, which he’d found tucked away in a smattering of second-hand stores in Toronto. Shahan realised he’d found his niche and decided to start scanning in images from these magazines of obscure fashion shows which had been lost in the mists of time, publishing them on the now-infamous Tumblr account archivings.net, which has evolved into the Instagram @archiving.stacks.

The year was 2013, and almost a decade later Shahan’s relentless research and dedication to community building around obscure avant garde fashion design has influenced a whole generation of fashion enthusiasts. “My intention was always to democratise the information, I was always trying to make it accessible for people, and just be kind of like a library of stuff that people wanted to see”, Shahan explains.

Seeing how others were profiting from a trend he had started, Shahan thought he’d get in on the action, but not in a conventional way. He approached Montréal-based boutique EFFE and asked if they’d like him to source a selection of second-hand designer pieces, to which he got a resounding ‘yes’. The result is a small selection of 17 pieces from obscure Japanese labels like Share Spirit, or the shoemaker Alfredo Bannister, advertised through a limited edition printed lookbook. The selection and lookbook, which was made available to buy either via Instagram or through the EFFE shop in July 2021, sold out within days.

Image courtesy of Twos

With such an influx of online sellers, it seems this kind of offline, physical approach is coming full-circle. London-based Josh Cook runs the IRL shop Twos in Seven Sisters. Twos began as a weekly sale in Josh’s bedroom, curated by style and price to cater to his friends. Then, as friends of friends began to come, the tight circle of Twos customers expanded.

When the pandemic hit Twos was forced to shut its doors for a while, before reopening at its current location in June this year. “It’s always been more about the community aspect”, Josh explains, which is why Twos has never had a functioning website — the social side of Twos couldn’t effectively be replicated online, operating more like a social hub than a retail space. Of course, people come to try and buy clothing, but as it’s only open every other weekend, some come just to hang out, play video games and drink a beer or two.

“It’s a reaction to where fashion’s got to these days,” Josh explains, “especially in the reselling game, it’s gone in a really cynical, banal direction — like who's going to find the next big thing, be that a brand or a mood”. Their Instagram is private, and the identities of customers are protected in any imagery that’s posted. It’s anti-hype in its approach. Because Twos is not yet fully operating online, it remains a space where clothing can just be enjoyed for what it is.

Image courtesy of Galtev

As varied as they are, these DIY sellers all seem to have a few notable things in common: their understanding and appreciation of the role that clothing can play in building communities and the desire to push the experience of a shop beyond just buying and selling.

These shops, however small, sit within a history of tiny boutiques which twist and bend the ways in which fashion can be experienced, from The House of Beauty and Culture’s workshop-meets-shop (which lasted only a few years but, according to legend, inspired Martin Margiela’s approach to deconstructing fashion), to legendary shop The Pineal Eye, which closed its doors in 2007. Even now, we can see that there is a renewed desire for small, experimental independent boutiques which focus on stocking DIY and artisanal brands, such as London’s APOC STORE or Chicago’s Lucky Jewel.

With vintage and second-hand fashion becoming a large part of the contemporary fashion enthusiast’s wardrobe, it’s only natural that the expansion of the shopping experience would extend into reselling. For now, these shops are small ventures but, with the right support, they might just become the model for a different kind of vintage shopping.

Article From & Read More ( The avant-garde fashion fans making resale more than shopping - i-D )https://ift.tt/3HOBpsh

Fashion

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The avant-garde fashion fans making resale more than shopping - i-D"

Post a Comment